Introduction

As financial professionals and analytic software lovers, the ability to efficiently load a large number of financial statements, and conduct an analysis has always been a key objective. In previous posts, Redwall Analytics worked with a 15-year time series of municipal Comprehensive Annual Financial Reports (CAFR) for 15 Fairfield County, CT towns Fairfield County Town Level Spending and Liabilities Gallop Since 2001. We also studied the worrisome long-term, time series of unfunded liabilities for all 169 Connecticut municipalities Connecticut City Unfunded Pension And OPEB Liabilities. We are probably most proud of our work replicating the complicated one-year (2016) spreadsheet analysis by Marc Joffe (Reason Foundation) and Mark Fitch (Yankee Institute) over the long-term Replicating Yankee Institute Risk Score Over 15 Years.

However, all of these were conducted using downloaded .csv data from the State’s website, not on the kind of structured XBRL data now required in real-time for public companies on the SEC’s Edgar website. Despite several attempts, XBRL had remained elusive up until now, but with daily practice, tasks previously beyond reach, suddenly become achievable.

Methodology

A good deal of credit and much of the code to extract XBRL data here from Edgar comes Aaron Mumala’s 2018 blog post: Accessing Financial Data from the SEC - Part 2. In addition, Micah Waldstein’s Parsing Functions in edgarWebR, as well as his edgarWebR package was helpful in understanding the structure and finding documents on the Edgar website, but the package doesn’t seem to be actively maintained, so we ultimately had to scrape the locations of the filings. Lastly, none of this would have been possible without Darko Bergant’s finstr and Roberto Bertolusso’s XBRL packages. To summarize the workflow to be described below, filing data is extracted with web scraping, the XBRL Instance Documents are downloaded and parsed into a list of data.frames with the XBRL package xbrlDoAll function, and finally, statements are organized into traditional Income Statements and Balance Sheets using the finstr package.

This will be the first in a three-part series. First, a quick walk-through to try to fill in some gaps from Aaron Mumala’s blog post and current documentation to help others up the learning curve with XBRL. Even better, we would welcome comments clarifying solutions to unresolved issues or even more efficient ways of extracting the same data than we have used. In the second part, we will use another free source of financial statement data (financialmodelingprep.com API) to pull 10-year’s of income statements for ~700 publically-listed pharma companies and explore R&D spending. Lastly, we will look to mine financial statement items for warning signs using metrics from a 2003 piece in the CFA Conference Proceeding.

Scraping Apple’s 10-K Filing Links from Edgar

We previously used edgarWebR for to find href links pertaining to filings, but because it stopped working with recent updates, so had to build the web scraper below. Below, we choose to query all past Apple XBRL 10-K filings up until last week. 20 results are available along with the web link (href) to each set of filings. Although filings prior to 2008 are available, these are in html format, and can’t be parsed with finstr and XBRL. A later effort may be made to retrieve these by scraping and parsing the html, but this is an advanced operation.

# Filter Edgar company search for "10-K" starting in "1990" in this case for AAPL (CIK 0000320193)

url <-

"https://www.sec.gov/cgi-bin/browse-edgar?action=getcompany&CIK=0000320193&type=10-K&dateb=1990&owner=exclude&count=25"

# Scrape filing page identfier numbers

filings <-

read_html(url) %>%

html_nodes(xpath='//*[@id="seriesDiv"]/table') %>%

html_table() %>%

as.data.table() %>%

janitor::clean_names()

# Drop pre XBRL filings

filings <- filings[str_detect(format, "Interactive")]

# Showing last 5 years

filings[1:5, c(1,3:4)] filings

1: 10-K

2: 10-K

3: 10-K

4: 10-K

5: 10-K

description

1: Annual report [Section 13 and 15(d), not S-K Item 405]Acc-no: 0000320193-19-000119 (34 Act) Size: 12 MB

2: Annual report [Section 13 and 15(d), not S-K Item 405]Acc-no: 0000320193-18-000145 (34 Act) Size: 12 MB

3: Annual report [Section 13 and 15(d), not S-K Item 405]Acc-no: 0000320193-17-000070 (34 Act) Size: 14 MB

4: Annual report [Section 13 and 15(d), not S-K Item 405]Acc-no: 0001628280-16-020309 (34 Act) Size: 13 MB

5: Annual report [Section 13 and 15(d), not S-K Item 405]Acc-no: 0001193125-15-356351 (34 Act) Size: 9 MB

filing_date

1: 2019-10-31

2: 2018-11-05

3: 2017-11-03

4: 2016-10-26

5: 2015-10-28There are generally about 15 elements in a filing package for a given year, as can be seen here for Apple in 2019. We only want to extract the XBRL Instance Document (XML), which is at the bottom of the table. In order to get this manually, we would have to click on the Document link. Instead, we show the steps to extract the actual links one by one using regex and again web scraping below. We also show the links for most recent five years below. Copy and pasting any of these links into the browser would show the 10-K for the relevant year.

# Extract filings identifiers with regex match of digits

pattern <- "\\d{10}\\-\\d{2}\\-\\d{6}"

filings <- filings$description

filings <-

stringr::str_extract(filings, pattern)

# Build urls for filings using filing numbers and Edgar's url structure

urls <-

sapply(filings, function(filing) {

# Rebuild URL to match Edgar format

url <-

paste0(

"https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/320193/",

paste0(

str_remove_all(filing, "-"),"/"),

paste0(

filing, "-index.htm"),

sep="")

# Return Url

url

})# Extract hrefs with links to 10-K filings

aapl_href <-

sapply(urls, function(url) {

# Pattern tomatch

href <- '//*[@id="formDiv"]/div/table'

# Table of XBRL Documents

page <-

read_html(url) %>%

xml_nodes('.tableFile') %>%

html_table()

# Extract document

page <- rbindlist(page)

document <-

page[str_detect(page$Description, "XBRL INSTANCE DOCUMENT")]$Document

# Take break not to overload Edgar

Sys.sleep(2)

# Reconstite as href link

href <-

paste0(str_remove(url, "\\d{18}.*$"),

str_extract(url, "\\d{18}"),

"/",

document)

# Return

href

})

# Show first 5 hrefs

aapl_href[1:5] 0000320193-19-000119

"https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/320193/000032019319000119/a10-k20199282019_htm.xml"

0000320193-18-000145

"https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/320193/000032019318000145/aapl-20180929.xml"

0000320193-17-000070

"https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/320193/000032019317000070/aapl-20170930.xml"

0001628280-16-020309

"https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/320193/000162828016020309/aapl-20160924.xml"

0001193125-15-356351

"https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/320193/000119312515356351/aapl-20150926.xml" Parse XBRL For all Instance Documents Using XBRL Package

We have not shown here, but XBRL parsing for US companies is governed by the schemas from the US GAAP reported Taxonomy, which are updated annually. These can be found here on the XBRL US website XBRL Taxonomy. By downloading the relevant .xsd file, removing the .xml suffix at the end and moving it to in the “xbrl.Cache” file created when you run XBRL, these problems were resolved for XBRL Instance Documents. Redwall spent quite a bit of time figuring out that we needed currency, dei, exch, country and currency files among others. We did this manually and by trial and error, but it seems likely that there is a better way. A more efficient solution might be found here on Stack Overflow XBRL Package Error in File.

Below, we use the xbrlDoAll function from the XBRL package to extract the financial statements using the links from the aapl_href list we made above. Note that we try(), because the function would fail on some of the documents and stop at that point.

# This chunk was run previously and stmt_list was saved for the purposes of this blog post

# Disable stringsAsFactors so XBRL parsing works

options(stringsAsFactors = FALSE)

# Run xbrlDoAll and store in stmt_list

stmt_list <-

# apply function to each element of href_list

lapply(aapl_href, function(doc) {

# Extract XBRL of using specified href

try(XBRL::xbrlDoAll(doc, cache.dir = "/Users/davidlucey/Desktop/David/Projects/xbrl_investment/xbrl.Cache"))

})

# Filter elements which failed to parse

stmt_list <-

Filter(function(x) length(x) > 1, stmt_list)As we have set it up in the code above, we loop through all Apple’s 10-K hrefs parsing with the XBRL package. This gives a list object for each annual reporting package, each in turn containing 9-10 data.frames (as shown below). Most of the data.frames relate to the taxonomy, governed by the .xsb files for that year. Starting in 2008, 10-Ks began being filed as “XBRL Instance Documents”, and these work seamlessly with the workflow described above. Around 2018, 10-K’s shifted to “Extended XBRL Instance Document” format, which we could not build into financial statements with finstr.

# Show one of extracted XBRL statements

summary(stmt_list[[3]]) Length Class Mode

element 8 data.frame list

role 5 data.frame list

calculation 11 data.frame list

context 13 data.frame list

unit 4 data.frame list

fact 9 data.frame list

definition 11 data.frame list

label 5 data.frame list

presentation 11 data.frame listIn the future, we would like to better understand the XBRL data structure, but again, it wasn’t easy to find much simple documentation on the subject. This post from Darko Bergant gives an excellent diagram of the structural hierarchy of the XBRL object Exploring XBRL files with R. He goes on in the same post: All values are kept in the fact table (in the fact field, precisely). The element table defines what are these values (the XBRL concepts, e.g. “assets”, “liabilities”, “net income” etc.). The context table defines the periods and other dimensions for which the values are reported.

Below, we show the first 50 lines of the “fact” list of the 2017 XBRL package. As noted above, data here is nested in levels, with the top level being the Balance Sheet, Income Statement, etc (again see Exploring XBRL files with R). It is possible to drill down to lower level items. Mr. Bergant also explains here how to for example extract a lower level item such as warranty information which wouldn’t be broken out at the top level How to get all the elements contained in the original XBRL?.

# Drill down on financial statement "fact" for individual year in stmt_list

stmt_list[[3]]$fact[1:10,c(2:4)] contextId

1 FD2015Q4YTD

2 FD2015Q4YTD_us-gaap_StatementEquityComponentsAxis_us-gaap_AccumulatedOtherComprehensiveIncomeMember

3 FD2015Q4YTD_us-gaap_StatementEquityComponentsAxis_us-gaap_CommonStockIncludingAdditionalPaidInCapitalMember

4 FD2015Q4YTD_us-gaap_StatementEquityComponentsAxis_us-gaap_RetainedEarningsMember

5 FD2016Q4YTD

6 FD2016Q4YTD_us-gaap_StatementEquityComponentsAxis_us-gaap_AccumulatedOtherComprehensiveIncomeMember

7 FD2016Q4YTD_us-gaap_StatementEquityComponentsAxis_us-gaap_CommonStockIncludingAdditionalPaidInCapitalMember

8 FD2016Q4YTD_us-gaap_StatementEquityComponentsAxis_us-gaap_RetainedEarningsMember

9 FD2017Q4YTD

10 FD2017Q4YTD_us-gaap_StatementEquityComponentsAxis_us-gaap_AccumulatedOtherComprehensiveIncomeMember

unitId fact

1 usd 748000000

2 usd 0

3 usd 748000000

4 usd 0

5 usd 379000000

6 usd 0

7 usd 379000000

8 usd 0

9 usd 620000000

10 usd 0Apply XBRL_get_statements via finstr Package to transform XBRL into Financial Statements

Next, we run finstr’s xbrl_get_statements on our stmt_list objects (ie: the XBRL Instance Documents) to convert the parsed XBRL objects into financial statements.

# This chunk was run previously and result_list was saved for the purposes of this blog post

result_list <-

lapply(stmt_list, function(stmt) {

try(xbrl_get_statements(stmt))

})Error : Each row of output must be identified by a unique combination of keys.

Keys are shared for 34 rows:

* 6, 8

* 5, 7, 9

* 49, 51

* 48, 50

* 55, 57

* 54, 56

* 11, 13

* 10, 12

* 25, 27

* 24, 26

* 59, 61

* 58, 60

* 29, 31

* 28, 30

* 63, 64, 66

* 62, 65As shown above, finstr’s xbrl_get_statements is unsuccessful on the first item (2019), which is the new “Extended XBRL Instance Document”, because of a problem with duplicate keys after the spreading the data.frame. It seems that finstr hasn’t been updated since 2017, so it likely has something to do with the problem. We asked for guidance on Stack Overflow Finstr Get XBRL Statement Error Parsing XBRL Instance Documents, but so far no luck. Also, it fails with the pre-2008 documents as expected, which were only available as html.

Catching Errors in Successfully Parsed Statements

There are many issues with XBRL including that companies classify items in differing ways, use different names for the same items and sometimes the there are errors in the calculation hierarchy. Classification differences will be challenging, but finstr has the check_statement function to show where there are calculation inconsistencies.

# Run check_statement on 2nd element of result_list (2018)

for(list in result_list[2]) {

print(lapply(list, check_statement))

}$ConsolidatedBalanceSheets

Number of errors: 0

Number of elements in errors: 0

$ConsolidatedStatementsOfCashFlows

Number of errors: 6

Number of elements in errors: 1

$ConsolidatedStatementsOfComprehensiveIncome

Number of errors: 0

Number of elements in errors: 0

$ConsolidatedStatementsOfOperations

Number of errors: 0

Number of elements in errors: 0 Above we can see that there are six errors in the “CashAndCashEquivalentsPeriodIncreaseDecrease” element_id in the 2017 Statement of Cash Flows. We can then drill down to see what those are. In this case, it is not a mismatch between the original data and the amount calculated as a check. The check is just not there (NA). We need to do further research to fully understand this function.

check <-

check_statement(result_list[[2]]$ConsolidatedStatementsOfCashFlows, element_id = "CashAndCashEquivalentsPeriodIncreaseDecrease")

# Calculated is NA

check$calculated[1] NA NA NALooking at Apple’s 2017 Balance Sheet Disclosure

Here we show the balance sheets for the first available document which is as of September 2018 (2019 does exist, but we were not able to parse that thus far). We could do the same for the Income Statement or the Statement of Cash Flows.

# Drill down to annual balance sheet from result_list

result_list[[2]]$ConsolidatedBalanceSheetsFinancial statement: 2 observations from 2017-09-30 to 2018-09-29

Element 2018-09-29 2017-09-30

Assets = 365725 375319

+ AssetsCurrent = 131339 128645

+ CashAndCashEquivalentsAtCarryingValue 25913 20289

+ AvailableForSaleSecuritiesCurrent 40388 53892

+ AccountsReceivableNetCurrent 23186 17874

+ InventoryNet 3956 4855

+ NontradeReceivablesCurrent 25809 17799

+ OtherAssetsCurrent 12087 13936

+ AssetsNoncurrent = 234386 246674

+ AvailableForSaleSecuritiesNoncurrent 170799 194714

+ PropertyPlantAndEquipmentNet 41304 33783

+ OtherAssetsNoncurrent 22283 18177

LiabilitiesAndStockholdersEquity = 365725 375319

+ Liabilities = 258578 241272

+ LiabilitiesCurrent = 116866 100814

+ AccountsPayableCurrent 55888 44242

+ OtherLiabilitiesCurrent 32687 30551

+ DeferredRevenueCurrent 7543 7548

+ CommercialPaper 11964 11977

+ LongTermDebtCurrent 8784 6496

+ LiabilitiesNoncurrent = 141712 140458

+ DeferredRevenueNoncurrent 2797 2836

+ LongTermDebtNoncurrent 93735 97207

+ OtherLiabilitiesNoncurrent 45180 40415

+ CommitmentsAndContingencies 0 0

+ StockholdersEquity = 107147 134047

+ CommonStocksIncludingAdditionalPaidInCapital 40201 35867

+ RetainedEarningsAccumulatedDeficit 70400 98330

+ AccumulatedOtherComprehensiveIncomeLossNetOfTax -3454 -150 Our results_list is nested, so not so easy to work with so we use the purrr package to flatten it into 35 financial statement objects including all of the balance sheets, income statements and cash flows for the period. The same first balance sheet we have already looked at is shown, but now at the top level so that the underlying data is easier to analyze and plot.

# Flatten nested lists down to one list of all financial statements for the 10 year period

fs <- purrr::flatten(result_list)

# Now the balance sheet is at the top level of fs instead of nested

fs[[2]]Financial statement: 2 observations from 2017-09-30 to 2018-09-29

Element 2018-09-29 2017-09-30

Assets = 365725 375319

+ AssetsCurrent = 131339 128645

+ CashAndCashEquivalentsAtCarryingValue 25913 20289

+ AvailableForSaleSecuritiesCurrent 40388 53892

+ AccountsReceivableNetCurrent 23186 17874

+ InventoryNet 3956 4855

+ NontradeReceivablesCurrent 25809 17799

+ OtherAssetsCurrent 12087 13936

+ AssetsNoncurrent = 234386 246674

+ AvailableForSaleSecuritiesNoncurrent 170799 194714

+ PropertyPlantAndEquipmentNet 41304 33783

+ OtherAssetsNoncurrent 22283 18177

LiabilitiesAndStockholdersEquity = 365725 375319

+ Liabilities = 258578 241272

+ LiabilitiesCurrent = 116866 100814

+ AccountsPayableCurrent 55888 44242

+ OtherLiabilitiesCurrent 32687 30551

+ DeferredRevenueCurrent 7543 7548

+ CommercialPaper 11964 11977

+ LongTermDebtCurrent 8784 6496

+ LiabilitiesNoncurrent = 141712 140458

+ DeferredRevenueNoncurrent 2797 2836

+ LongTermDebtNoncurrent 93735 97207

+ OtherLiabilitiesNoncurrent 45180 40415

+ CommitmentsAndContingencies 0 0

+ StockholdersEquity = 107147 134047

+ CommonStocksIncludingAdditionalPaidInCapital 40201 35867

+ RetainedEarningsAccumulatedDeficit 70400 98330

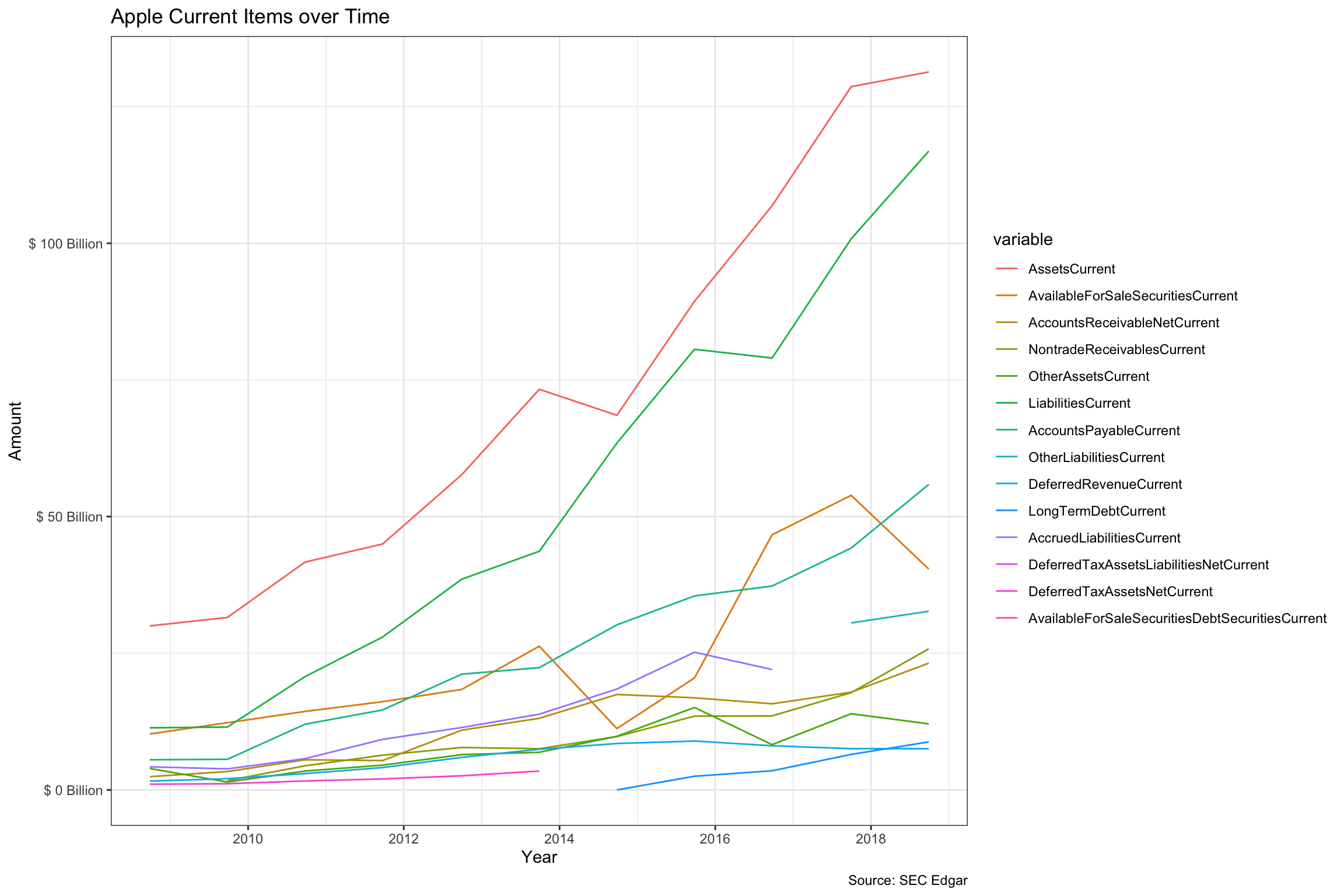

+ AccumulatedOtherComprehensiveIncomeLossNetOfTax -3454 -150 Next, we can graph the evolution of “Current” items over the 10-year period. Note that in 2017, Apple started calling them “Consolidated Balance Sheets”. Prior to that, they were named “Statements of Financial Position Classified”. Hence, we had to regex match using both “Balance” and “Position” to get the relevant documents for the full period. This clearly cumbersome and difficult to do at scale on a larger number of companies. We can see that both current assets and liabilities have tripled over the period.

# Regex match list items matching "Balance" and "Position" and rbind into bs (balance sheet)

bs <-

rbindlist(fs[str_detect(names(fs), "Balance|Position")], fill = TRUE)

# Drop any duplicates with same endDate

bs <- unique(bs, by = "endDate")

# Function to scale y axis label

scaleFUN <- function(x) paste("$",x/1000000000,"Billion")

current <- names(bs)[str_detect(names(bs), "Current")]

# Tidy and ggplot from within data.table bs object coloring variables

bs[, melt(.SD, id.vars = "endDate", measure.vars=current)][

][!is.na(value)][

][, ggplot(.SD,

aes(as.Date(endDate),

as.numeric(value),

color = variable)) +

geom_line() +

scale_y_continuous(labels = scaleFUN) +

labs(title = "Apple Current Items over Time",

caption = "Source: SEC Edgar") +

ylab("Amount") +

xlab("Year") +

theme_bw()]

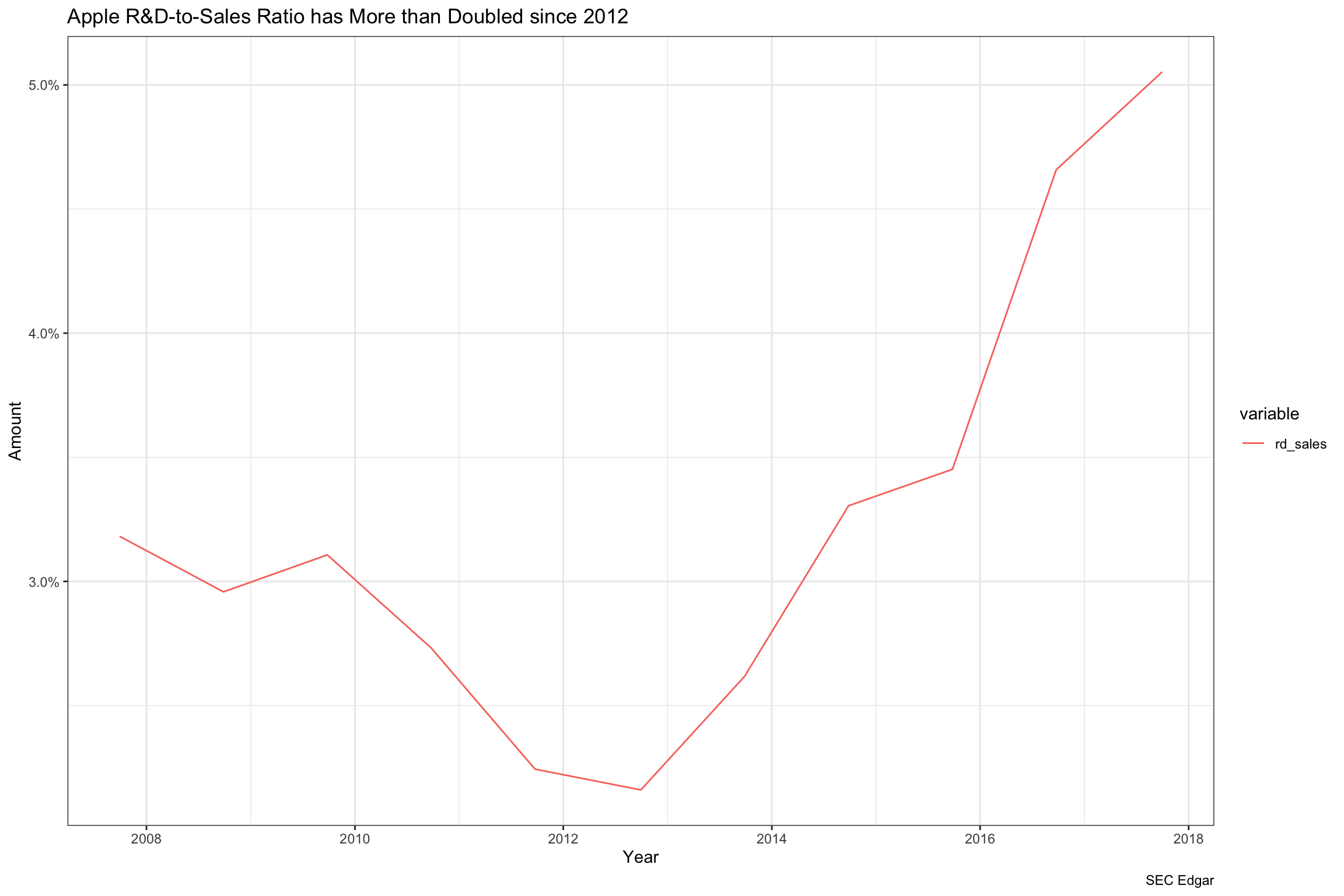

We are curious about R&D spending over time, so here we took the income statements which again used changing names (Statements of Income and Statements of Operations) over time. It looks like Apple reduced its R&D spending sharply after the iPhone launch, but has ramped it up again to launch the wearables business. We will use this strategy to extract specific balance sheet and income statement items in Part 3 to mine for warning signs.

# Regex match list items matching "StatementOFIncome" and StatementsOfOperations", and rbind into is (income statement)

is <-

rbindlist(fs[str_detect(names(fs),"StatementOfIncome$|StatementsOfOperations$")], fill =

TRUE)

# Drop NA rows

is <-

is[!is.na(SalesRevenueNet)]

# Drop previous year's which are dupes

is <-

unique(is, by = "endDate")

# Mutate R&D to sales ratio variable and select columns needed

is <-

is[, rd_sales :=

ResearchAndDevelopmentExpense / SalesRevenueNet][

][, .(endDate, rd_sales)]

# Tidy and ggplot within data.table is object

is[, melt(.SD, id.vars = "endDate", measure.vars=c("rd_sales"))][

, ggplot(.SD, aes(as.Date(endDate), as.numeric(value), color = variable)) +

geom_line() +

scale_y_continuous(labels = scales::percent) +

labs(title = "Apple R&D-to-Sales Ratio has More than Doubled since 2012",

caption = "SEC Edgar") +

ylab("Amount") +

xlab("Year") +

theme_bw()]

Conclusion

After spending the few years solving many problems in R, the volume of discussion about XBRL still seems surprisingly sparse for such a big potential use case. In addition, most of development at least in R seemed to stop cold in 2017. It will be interesting to learn if this is because most the people who look at financial statements generally don’t use XBRL in analytic software yet, or because it is too inefficient to get clean data in a usable form. In the end, Aaron Mumala suggested that downloading and parsing XBRL from Edgar was probably still not ready for prime time.

Admittedly, the challenges discovered in this exercise because of changing statement names, financial statement items, data formats, we wondered if the SEC Edgar XBRL disclosures are suitable for a large scale analysis. Many providers charge for data parsing and cleaning, and it may be worth paying for, especially if real money will be involved. In Part 2 of this series, we will look at using a free outside provider of financial statement data (Financial Modeling Prep) and see what we find.